|

5/31/2019 Continuing the Discussion on Human Capital and Sustainable Development and the evolving lessons about Human DevelopmentRead Now Some interesting issues were raised in reaction to the May 10, 2019 Blog, “Human Capital and Sustainable Development”. Among them were those requiring that attention be paid to options ( among others) that are:

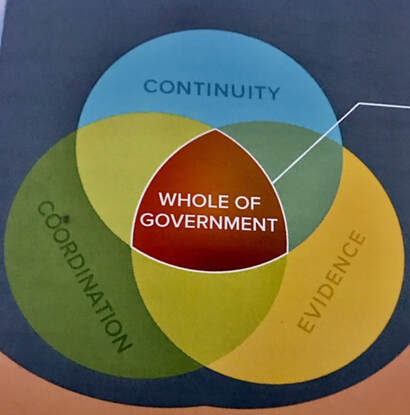

These are all probing concerns that make adequate responses, challenging Responding to Institution-centric thoughts and practices Over the many years, the world has been galvanized around targets set by key international institutions. Notwithstanding their flaws, the UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) 2000-2015 and its successor, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 2015-2030 have established targets around which countries have measured progress and criteria for funding international causes. The Global Fund for AIDS, Malaria and TB (GFATM) is a very important example of using a standard metric, level of economic status and burden of disease to direct international assistance to check the spread of these diseases. The UNDP-led Human Development Index (HDI) in the 1990s created a useful basis for combining the traditional GDP measure of development with other social indicators such as human rights, governance, educational attainment, and health outcomes that ranked the human development profiles of countries. Among the 58 countries in the very high HDI category led by Norway , Switzerland, Australia and Ireland in that order are the Bahamas at 54 and Barbados at 58. These institutional-centric metrics have a tendency galvanized performance enhancing measures among countries in the UN system around common goals and targets. Rectifying Sociological gaps The GOFAD blog (May 24, 2019) reviewing Thaler and Sustein’s book, Nudge provides an apt illustration of how interventions through behavioral research can fill ‘the sociology gap’ in the institutional-centered metrics. The approach is deemed to help people, government agencies, companies and charities to make better decisions. These decisions are wide ranging: from choosing a credit card, to reducing harmful pollution, avoiding fatty foods, and making long term plans that affect human development. At the same time, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for example, were created and adopted by United Nations through an extensive process of technical and civil society focus group sessions. They provided an expansive blueprint on what countries need to do to reduce poverty and hunger, education and gender inequalities; enhance health and well-being and access to clean water and sanitation; accelerate responses to achieve affordable and clean energy and pave the way for decent work and economic growth and the prospects for peace, security, social justice and global social justice. The lessons from Investments in Human Capital The Human Capital Project being promoted by the World Bank Group provides a useful metric that helps to standardize links between human and economic development. It nurtures a whole of Government approach that revolves around three principles: (i) sustaining efforts across the political cycles; (ii) coordinating across government (agencies); and (iii) designing policies and programmes that use and expand the evidence base. The results illustrate that “while adopting any one of these strategies help build human capital, countries that have implemented all three in tandem are often among those that have made major strides in improving human capital outcomes". The Report from the Human Capital Project series No 4 (April 2019) provides concrete evidence of the lessons learned. Singapore, for example, created a world class education system with some of the highest learning outcomes. Whereas in 1950, an adult averaged 2.1 years of formal schooling, by 2010 this rose to 10.6 years as a result of an educational policy that incorporated private and public schools into a unified national education system, with direct state funding and generous grants-in-aid. By 1974, Singapore through a government driven investment in a learning economy, achieved universal primary education. By 1990, there was a 44 percent enrollment in secondary education, and a robust vocational training sector which led to a consolidation of the training centers into an Institute of Technical Education (ITE). At the university level, employers were engaged in curriculum and course design to ensure the response of graduates to market needs. In Peru, a long term vision to reduce stunting of children paid great dividends. It reduced the chronic rate of malnutrition in children from 28% to 13% between 2005 and 2016. Its policy stressed that malnutrition is wider than just food distribution and includes water, sanitation, access to health services, education and empowerment of women in poor remote areas and rural communities. These combined are critical components of reducing stunting, but have been enhanced by involving municipal governments in the administration of the programme with the Ministry of Economics and Finance monitoring and evaluating the process through a results-based approach. Other examples given in the April issue of Human Capital include Ireland and the Republic of Korea. In Ireland, investment in human capital concentrated on linking jobs and skills to transform a mainly agrarian economy in the 1970s into a leader in the new global frontier of electronics and information by 2000. Its Expert Group for Future Skills Needs, established in 1997, was responsible for linking educational outcomes with needs of various industries and sectors, bench marked against international standards. At the same time lessons from the Republic of Korea show that implementing all three Human Capital strategies can lead to dramatic transformations. This is illustrated in the implementation of sustained investments in health and education complemented by sound economic policies and paying attention to population growth (the demographic dividend). It led to a spectacular 6.7% average annual growth over a forty year period. Drawing Conclusions There is however much more to the Human Capital Project that needs to be further explored. There is no better time to call on local and international governments, as well as the private sector to direct more investment into the long term and sustainable development of individuals. This must take into consideration both their capabilities (skills, knowledge and behaviours) and their capacities (self-leadership, confidence, motivation, resilience and mindset). But herein lies a compounding issue that no metric of human development can adequately explain. It is the effect of culture on the consciousness about life and social relations in both economic and political activities in a society. It includes the intangibles like values, social consciousness and morality. It is difficult to build a culture in isolation of social reality. Culture has its own particularity and will evolve with economic and political practices. These in turn all effect how we interpret the essence of human development.

2 Comments

6/6/2019 06:55:59 am

The blogs raise several interesting scenarios in the determination of the path to development. Highlighting the strategic importance of the linkages between education, and health and human progress from the various dimensions of the UN 2030 development agenda they provide development practitioners with crucial insights on the significance of the international development agenda. Most studies and official reports stress that increased productivity is the most effective way in stimulating and enhancing sustained growth.

Reply

Edward Greene

6/7/2019 03:28:21 am

Thank you Garfield for these pertinent comments Since they are also relevant to the blog on CARICOM HRD and investment in Human Capital I plan to copy it for readers of the 7/6/19 blog to see &

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Details

AuthorEdward and Auriol Greene Directors, GOFAD. Archives

April 2022

Categories |

Global Frontier Site Links |

Contact InformationEmail: [email protected]

Twitter: @GofadGlobal |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed